On June 17, 1631, the 38-year old chief consort of Shah Jahan, head of the Mughal Empire, was giving birth to their 14th child in the central Indian city of Burhanpur.

It had been a long and extremely difficult labor– more than 30 hours in total. But the consort persisted and gave birth to a healthy baby girl. The consort herself, unfortunately, succumbed to uncontrollable postpartum bleeding, and she passed away that same day.

Her name was Mumtaz Mahal. And her husband the Emperor was so bereaved that, after a year-long period of mourning, he commissioned a palatial mausoleum to house her tomb.

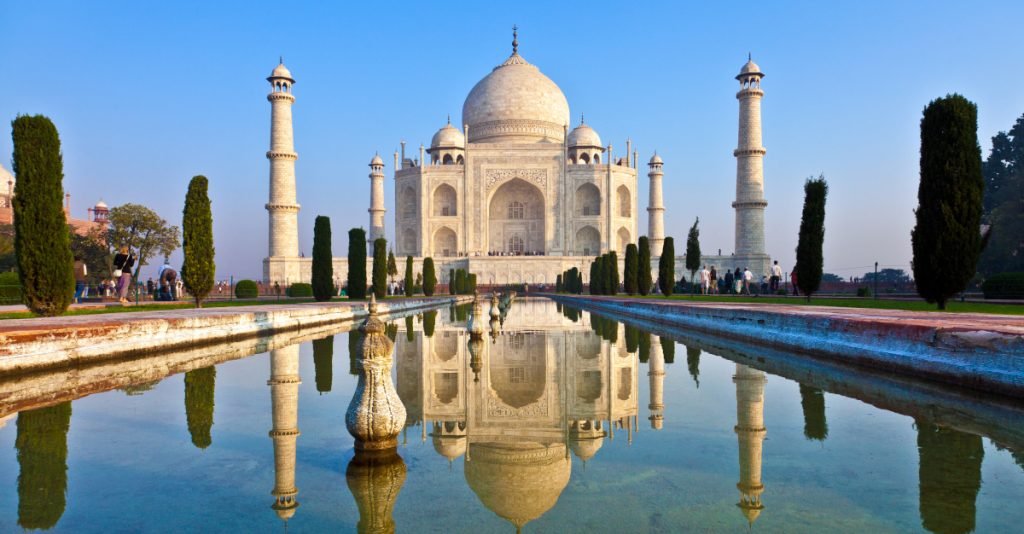

We know this tomb today as the Taj Mahal. And Shah Jahan spared no expense on its grandeur. According to the scrupulously kept financial records of the time, the cost of the Taj Mahal totaled precisely 41,828,426.47 silver Rupees. Based on the today’s gold and silver prices, that works out to be more than $3 billion in today’s money.

Now, I’m sure Shah Jahan loved his wife very much. But that’s a lot of money to spend on a tomb… especially when the money comes from the public treasury.

But this sort of profligate spending was pretty typical of the Mughal Emperors at the time.

The Mughal Empire had only been founded roughly 100 years before, in 1526. And it rose to prominence under the reign of Akbar the Great during the late 1500s.

Akbar tripled the size and wealth of the Mughal Empire until it included virtually all of India, Pakistan, and parts of Bangladesh and Afghanistan.

Akbar also ensured that economic freedom reigned. He cut taxes. The coinage was stable. Infrastructure was highly advanced. People were free to engage in commerce and trade.

Akbar also held government bureaucracy to a minimum, and even kept his personal household spending quite low.

He famously ruled with a staff of just four ministers, and he set an example of routinely hiring people based purely on their talent, irrespective of someone’s religion, nationality, or class.

As a result, the Mughal Empire became a financial powerhouse, responsible for roughly 22% of global GDP. (This is approximately the same as the US is today.)

The empire quickly became known for its unimaginable wealth, and European travelers marveled at the Mughals’ high standard of living.

Naturally, the wealth didn’t last. The emperors who followed Akbar did not continue his policies of freedom, tolerance, and conservative spending.

Akbar’s son Jahangir was a cruel, drunken degenerate who reveled in flaying his political opponents; he also ballooned the expenses of his imperial court by establishing a harem of 6,000 women.

(The harem’s administrator was the emperor’s favorite wife– a woman he married after brutally murdering her first husband.)

Jahangir’s son, Shah Jehan, was even more intemperate. He came to power by slaughtering his brothers, and then quickly raised government spending to epic levels.

In addition to the Taj Mahal, Shah Jehan built dozens of other lavish palaces, and he spent indiscriminately on other personal luxuries like jewelry.

He raised taxes and poisoned the economy with armies of bureaucrats. Shah Jehan was also highly intolerant of other religions and ideologies, and he imposed a special tax on all individuals who did not convert to his Muslim faith.

Shah Jehan was violently overthrown by his son Aurangzeb, a fanatic who sought to eradicate every other faith except for his own. He tore down monuments, smashed statues, and closed schools which did not conform to his ideology.

As Emperor, Aurangzeb raised taxes and accelerated expansion of regulation and government bureaucracy. He also constantly provoked foreign enemies and sunk a great deal of the Empire’s sagging treasury into a never-ending state of costly warfare.

Ironically, though, due to his personal faith, Aurangzeb was a pacifist at home. He frequently refused to enforce the laws and punish crime. Eventually Aurangzeb became legendary for his clemency and forgiveness, and criminals thrived under his reign.

Aurangzeb died in 1707. And just 17 year after his death, the Mughal Empire had disintegrated into fragments.

The Empire’s rise to wealth and prominence over just a few decades in the 1500s was astonishing. Its rapid decline was even more extraordinary. But it’s not hard to understand.

Between peak and decline, the Empire experienced terrible leadership. Weak and incompetent emperors spent lavishly, expanded the bureaucracy, raised taxes, increased regulation, and waged war. Some of those wars ended with humiliating defeats, resulting in a loss of national prestige.

They trampled on individual and economic liberty. They formalized extreme ideological intolerance and encouraged social divisions. They canceled, sometimes violently, anyone who didn’t espouse their beliefs.

They didn’t bother enforcing their own laws, and they let the lawless reign. They lost the ability to transfer power in an orderly manner between successive rulers.

They failed to protect their borders from foreigner invaders– most notably the British East India Company. And they absolutely failed to recognize that rival powers around the world were rising and would take their place.

They foolishly and arrogantly assumed that their wealth and power would last forever. It didn’t. It never does.

This theme is as old as human civilization itself, and we can see many of the same extravagances and follies from the Mughal Empire in our world today.

This time is not different, and it’s why diversifying internationally makes so much sense… why having a Plan B makes so much sense.