When I was about five years old in the early 1980s, my dad brought home our first computer.

I’ll never forget it– it was an clunky IBM with a tiny, orange, monochromatic monitor, and dual floppy disks. It had 640 kilobytes of RAM, and no hard disk.

I loved it. With that computer I learned how to program, how to navigate a command-line interface, how to design algorithms, and how to solve constant problems… because it was ridiculously buggy and would break down all the time.

It was also painfully slow. The boot-up process could easily take an hour, from the time I flipped on the power switch, to the time I saw the ‘DOS prompt’.

Sometimes I think that computer is a great metaphor for the global economy. Turning it off is nothing; you flip the switch and the power goes off. But starting it back up again takes a long time. And the process isn’t so smooth– sometimes it crashes during bootup.

Last March when the Great Plague was upon us, nearly every industry, in nearly every country in the world, practically shut down.

And many businesses went bust, never to return.

Eighteen months later businesses have largely reopened. But like my old computer, the reboot process has been riddled with critical errors and system failures.

For example, right now there are countless businesses in industries from retail to manufacturing that are experiencing severe labor shortages. Supply chains around the world are breaking down, resulting in product shortages and major transportation bottlenecks.

The end result of this dumpster fire is that prices are soaring. And I wanted to spend some time today connecting the dots to help explain some of these important trends.

Let’s go back to last March again when everything shut down. You probably recall that dozens of large companies declared bankruptcy, like Nieman Marcus, GNC, JC Penny, etc.

But there were other companies that went bust which most people have probably never heard of. They were in more mundane, less sexy industries… like corrugated paper and wood pulp.

Yet while their demise was hardly noticed, it turns out they would have a significant impact on the global economy.

Global shipping demand surged last year in ways that had never been seen before. Suddenly, instead of efficient supply chains shipping goods to large marketplaces (like retail and grocery stores), consumers wanted everything delivered to them.

While the total volume of shipping was largely the same (or even less) than previous years, the number of individual shipments increased dramatically.

In other words, instead of a single large shipment to a store or supermarket, companies were making thousands of tiny shipments to individual consumers.

This meant more trips… and more packaging. More cardboard boxes. More plastic wrap. More plastic containers. More Styrofoam.

And the prices for all of these materials has spiked.

The price for polyethylene, for example, which is used extensively in shipping, has increased from $820 per ton to $1,850 per ton. Polypropylene prices are also up from $1,100 per ton to $1,770 per ton.

It’s a similar trend with cardboard and corrugated paper. And these price increases aren’t simply due to high demand either.

Supply has fallen. Last March when a number of wood pulp producers went out of business, no one noticed and no one cared. But it turned out that more than 10% of all North American paper capacity vanished, practically overnight, just before demand started to surge.

And this capacity cannot be simply turned on again with a flip of a switch. It takes a lot of effort to resurrect a bankrupt factory, to re-hire and re-train workers. (We’ll get to the worker issue in a moment.)

It’s a similar trend around the world– foreign factories have closed, and those that remain open are struggling to retain workers and operate under strict COVID protocols. Manufacturing efficiency is way down as a result, so they’re not producing enough supply to keep up with demand.

Then there are the actual shipping problems– the crazy delays, especially on the West Coast of the United States, that prevent container ships from delivering their cargo.

It’s not that there aren’t enough ships in the world; in fact, the total global capacity in terms of TEUs, or 20-foot Equivalent Units, is slightly higher than pre-pandemic.

But a range of factors, including COVID rules and union regulations, means there’s a shortage of maritime crew to operate the vessels. There’s also a shortage of dockworkers, truck drivers, forklift operators, etc. at the ports.

This is especially true in California, whose regulatory environment makes port operations extremely difficult and inefficient.

Yet sadly for the United States, California’s ports are the busiest and most important in the country; most of the seafreight from China is offloaded at the Port of Long Beach or Port of Los Angeles, so bottlenecks there cause a major ripple effect across the country.

Right now there is a backlog of ships waiting to unload their cargo in southern California.

This makes the COVID policies of California especially important for the rest of the United States; whatever Gavin Newsome decides has a huge impact on the national economy.

Labor is obviously another major issue in this messy economic reboot.

Thanks to a steady digest of mass media Covid hysteria, there are still plenty of people who are terrified to leave their homes and go to work.

Moreover, there are so many people who got used to being home over the past 18-months, that now they only want a job where they can work from home.

This is a major problem for businesses… and why it’s so hard for restaurant companies, fast food joints, retail shops, factories, etc. to find workers. People would rather stay home.

The government hasn’t exactly been helpful in this department when they were paying outsized unemployment benefits to encourage everyone to stay home. That effect is lingering.

There’s another trend at work here, though.

For the last several years, politicians have been fighting hard to bring manufacturing jobs back to the United States.

It turns out that no one really wanted those jobs to begin with.

Younger people in particular don’t have as much interest in those sorts of traditional jobs; they’d rather be ‘influencers’ and make their money posting butt selfies and snapshots of their contrived lifestyle.

This was already becoming an issue prior to COVID; large companies– especially those in industries that were considered unappealing to Gen Z– were complaining how difficult it was to hire, train, and retain young workers. Now it’s borderline impossible.

Businesses also have to compete with the government for labor, which has gobbled up workers and put them to work as ‘contact tracers’.

And retail companies that are lucky enough to find employees are forced to misallocate those scarce resources to do unproductive tasks, like checking everyone’s ‘papers’ when customers walk through the door.

And then, of course, if a business has been able to navigate all of those crazy obstacles, Hunter Biden’s dad is now forcing you to fire any worker who hasn’t been [unmentionable word — thanks Google].

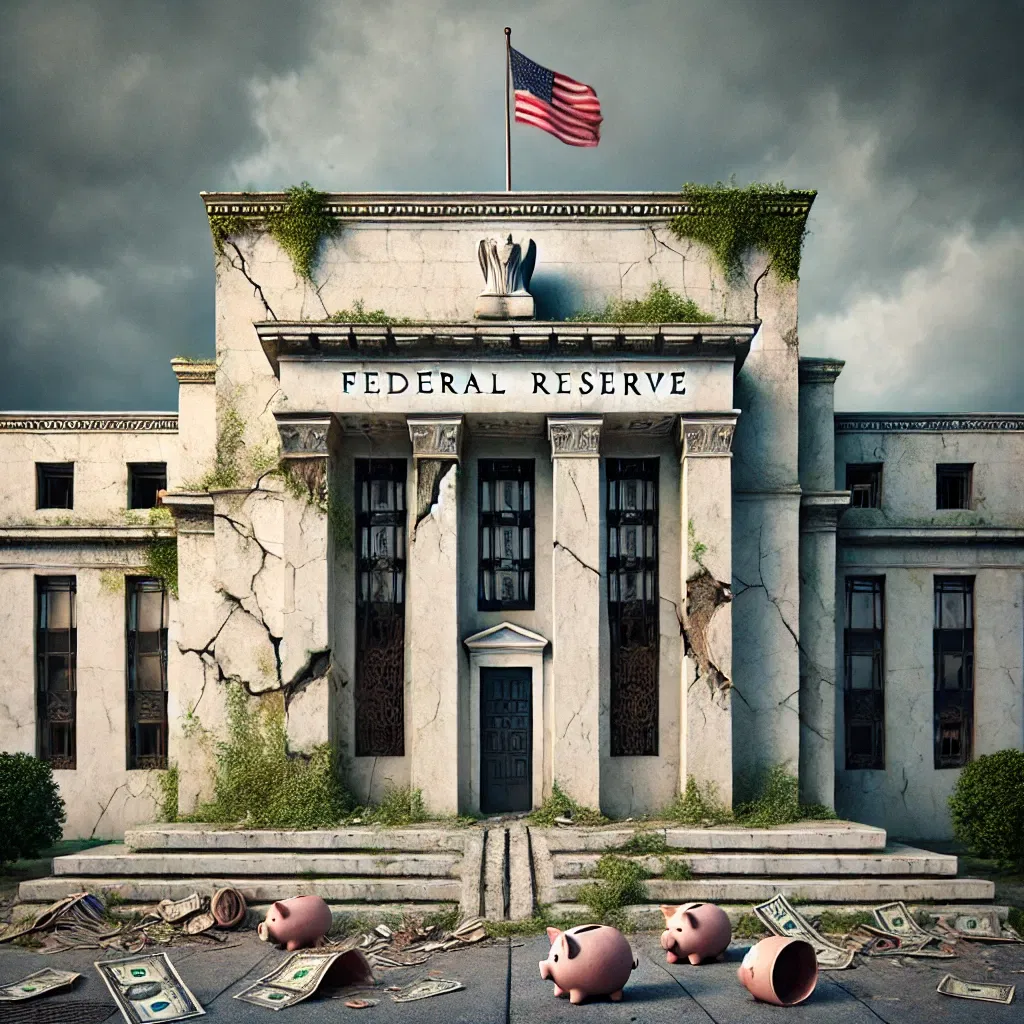

On top of all of the above is the Federal Reserve’s monetary blowout. They’ve printed trillions of dollars over the past 18 months to ‘support the economy’. Yet even though the unemployment rate is down to 4.8%, they’re STILL printing at least $120 billion per month in new money.

All that new money has helped fuel giant asset bubbles in stocks, bonds, property, and commodities. Energy prices in particular have risen sharply, and this tends to cause all other prices to rise.

The result of all of this insanity is inflation. Lots of it.

The problem is that most of these trends are not going away anytime soon. The Fed may start to taper its money printing. But they have very little room to raise interest rates meaningfully to combat inflation.

Plus the labor issues, government policy, shipping, manufacturing shortages, etc. are going to last for a while.

In fact, you’d think the correct government policy right now would be to create incentives for people to work, to create new businesses, and to invest in new technology that could automate and clean up the bottlenecks.

At a minimum you’d think they’d stay the hell away and let capitalism do its job.

After all, free market competition is one of the greatest tools to fix any economic woes, especially inefficiencies and resource misallocation.

Yet all of the policies they’re proposing are anti-competitive and anti-market. They want to create DISINCENTIVES to form businesses and make investments.

It’s the exact opposite of what they should be doing.

(This is what happens when you put a socialist in charge of writing the budget.)

So the next time one of these politicians or central bankers say that inflation is ‘transitory’, you can be certain they’re completely clueless about what’s happening in the real world.