Maximilian Bern had saved up 100,000 German marks for what should have been a modest, but comfortable retirement.

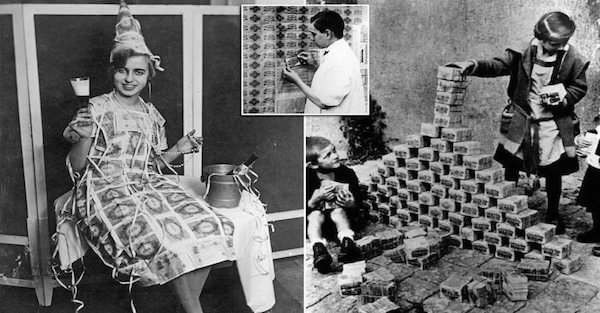

But in 1923, he withdrew every last cent, and spent it all on one purchase: a subway ticket.

He rode around his city one last time before returning home, and locking himself in his home, where he died.

He didn’t kill himself. He starved to death… simply because he could no longer afford food. A single egg at the market would cost millions of marks, more than Maximilian Bern had saved over his entire life.

This was one of the most famous episodes of hyperinflation, certainly in modern history.

In the wake of World War One, Germany (known as the Weimar Republic) was completely broke.

The War to end all Wars had bankrupted them; and on top of losing the war, Germany was forced to make ‘reparation payments’ to the victors, including France, the UK, etc.

That took Germany’s overall war debt to impossible levels. So in a feeble attempt to keep the economy afloat and meet its war debt obligations, the German government printed massive amounts of paper money.

Prior to World War I, one US dollar was worth 4.2 German marks.

By 1923, a single US dollar was worth 4.2 TRILLION marks.

We’ve seen this in our own lifetime in places like Zimbabwe, and now Venezuela.

I remember the first time I went to Venezuela the official exchange rate was four bolivars to the US dollar—and the black market rate was eight to one.

The next time I went it was hundreds, then thousands and then tens of thousands of bolivars to just one US dollar.

Around two years ago when I was in Caracas, I changed a few hundred dollars and received an entire suitcase full of money in return. (I didn’t get to keep the suitcase).

The rate of inflation now in Venezuela was as high as 1.6 million percent last year. It’s difficult to even imagine what that means.

But we’ve all heard these horror stories of hyperinflation. Everyone seems to understand the horrible effects it has on the economy and individuals.

But somehow we’re supposed to believe that a little bit of inflation is somehow good for the economy. I find that absurd.

The Federal Reserve tries to keep the inflation rate between 2% and 3% per year. That might seem like chump change, but it adds up.

Even John Maynard Keynes, whose works underpin the foundation of modern central banking, once wrote:

“By continuing the process of inflation governments can confiscate secretly and unobserved an important part of the wealth of their citizens.”

It’s so subtle because it only steals a little at a time from you, over the course of many years.

But again, over time, it adds up.

As we’ve seen over the last couple decades, wages have not kept pace with inflation. So year after year, the average workers loses a little bit of prosperity.

1-2% per year doesn’t really matter. A decade or two of this, however, really has an impact.

We keep hearing these Bolshevik politicians calling for a Wealth Tax. They obviously fail to realize that a wealth tax already exists. It’s called inflation.

Ironically, Keynes continued to write about inflation, saving, “And while the process [of inflation] impoverishes many, it actually enriches some.”

And that’s true. Back in Germany’s hyperinflation days, there were a handful of sophisticated people who saw the writing on the wall. They knew that the government could never pay its debts, and that they would print money and debase the currency.

These guys set up their investments in a way to actually profit from hyperinflation.

Donald Trump famously referred to himself during the 2016 Presidential campaign as the “King of Debt” because he has been able to profit by borrowing money.

These investors in the Weimar Republic were known as the Kings of Inflation. And Hugo Stinnes was the King of Kings.

Stinnes had positioned himself perfectly for when hyperinflation hit.

He borrowed vast amounts of German marks and poured them into his coal, steel, and shipping companies.

He also kept gold in Switzerland, and made investments in foreign markets.

When hyperinflation hit, Stinnes was able to pay back his debts with the massively devalued German mark.

But Stinnes’ hard assets weren’t affected by the hyperinflation. They held their value. His businesses and investments flourished, making him one of the wealthiest men in the world.

This is just a reminder that, no matter what happens in financial markets or the global economy, there are always winners and losers.